Billions Spent on Mass Culling for Bird Flu

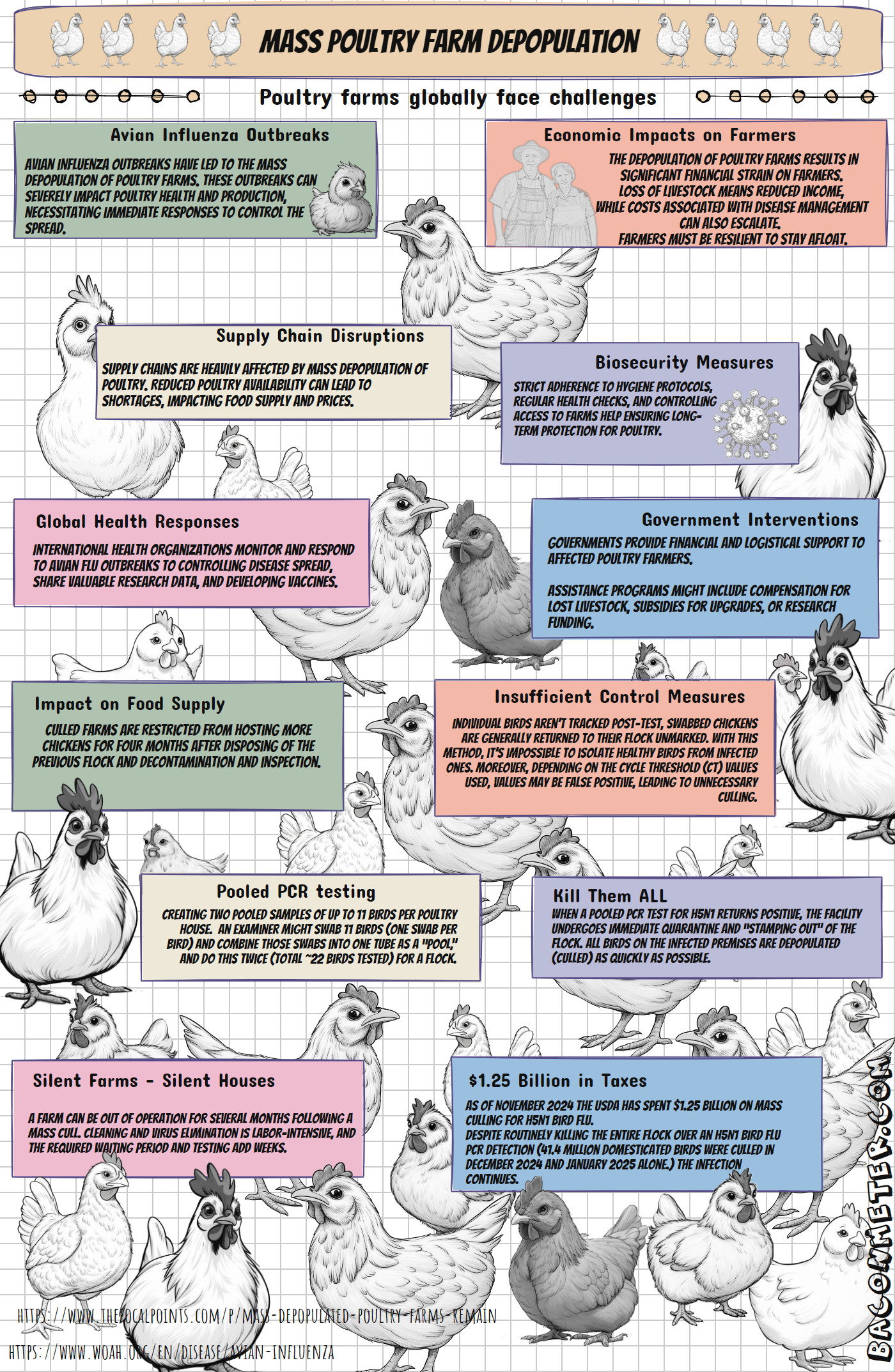

Protocols that mandate the mass culling of entire flocks upon detection of the virus, via pooled PCR tests, are overly aggressive and economically disastrous.

Farms remain non-operational for approximately four months after culling due to stringent cleaning and disinfection requirements, exacerbating disruptions to the food supply chain and contributing to egg price spikes, such as the 45-year high reported in January 2025.

The policy does not allow for separating healthy birds from infected ones, leading to the unnecessary destruction of potentially uninfected poultry. This "stamping out" approach is contrasted with evidence suggesting that many chickens can survive H5N1 and develop natural immunity, which could help curb future outbreaks without mass depopulation.

References a study by Garg et al., claiming that 100% of human H5N1 cases linked to poultry stem from the chaotic culling process itself, not from normal farm operations.

USDA's $1.25 billion expenditure on culling-related indemnity payments since the H5N1 outbreak began in 2022, has been a wasteful use of taxpayer money that incentivizes farmers to comply with a flawed strategy.

Suggested alternatives like targeted culling or vaccination are possible, but noted the USDA’s recent conditional approval of an H5N2 vaccine, though it warns of potential risks like the emergence of new viral strains from "leaky" vaccines.

PCR tests might be considered a poor choice for detecting infections, particularly as inferred from the piece:

Over-Sensitivity and False Positives: PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) tests amplify tiny fragments of genetic material, which can detect viral RNA even in minute quantities. The article mentions "pooled PCR detections," suggesting that samples from multiple birds are combined, potentially flagging an entire flock as infected based on a single or low-level detection. This high sensitivity may lead to false positives or exaggerate the presence of viable, transmissible virus, triggering mass culling when the actual threat might be minimal.

Lack of Clinical Context: A common critique of PCR is that it detects genetic material without distinguishing between active, infectious virus and residual, non-infectious fragments. In the poultry context, this could mean healthy birds are culled unnecessarily if the test picks up remnants of past exposure rather than current disease, a point hinted at by the suggestion that birds can survive and develop immunity.

Broad Application Without Specificity: The use of "pooled" testing, as noted in the article, implies a lack of granularity—individual sick birds aren’t identified, and entire flocks are condemned based on a collective result. This blunt approach overlooks the possibility of isolating infected birds, amplifying the economic and ethical downsides of mass depopulation.

Triggering Extreme Measures: The article critiques the policy tied to PCR results, where a positive test leads to immediate, irreversible action (culling and months-long farm shutdowns). This suggests that PCR, while accurate for detection, becomes problematic when paired with inflexible protocols that don’t account for the scale of infection or alternative management strategies.

In essence, the articles indirectly frames PCR tests as problematic not because they fail to detect H5N1, but because their sensitivity and the way results are interpreted and acted upon in U.S. biosecurity policy lead to overreactions—destroying healthy animals, disrupting food supply, and costing billions—without effectively controlling the virus.

Read More The Focal Points The Focal Points WOAH World Organization for Animal Health