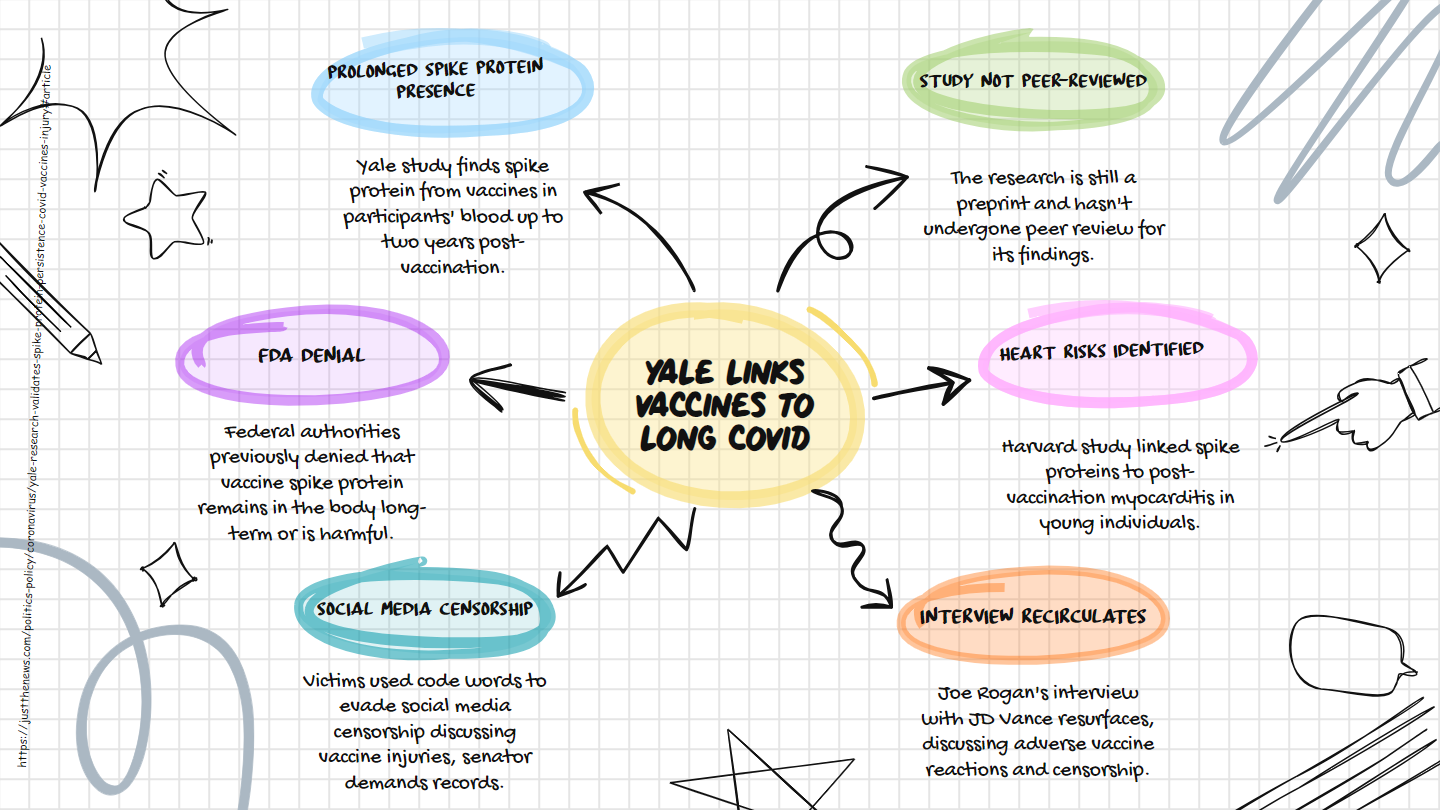

Yale links vaccines to Long Covid

A Yale University study, published as a preprint on February 18, 2025, has found that spike protein from mRNA COVID-19 vaccines can persist in the blood of some vaccinated individuals for up to nearly two years (600-700 days), far longer than the previously reported eight weeks.

Conducted by immunobiologists at Yale, the research suggests that this persistence may contribute to a condition termed post-vaccination syndrome (PVS), characterized by chronic symptoms similar to long COVID, such as fatigue and brain fog, in a small subset of vaccinated people who were never infected with the virus.

The study involved 42 PVS participants and 22 healthy controls, revealing higher spike protein levels and distinct immune profiles in those with PVS. This finding challenges earlier assurances from federal health authorities, like the FDA, which denied that vaccine spike protein lingers or is toxic.

The research also notes social media censorship of vaccine injury discussions and calls for further investigation into PVS, despite its lack of official recognition by health authorities. The authors acknowledge the study's preliminary nature, as it awaits peer review, but it adds to growing evidence of potential vaccine-related complications.

The Yale University study, uploaded as a preprint on bioRxiv on February 18, 2025, provides significant insights into the persistence of spike protein generated by mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (such as those from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) in the bloodstream of some vaccinated individuals. Authored by a team of Yale immunobiologists, including Akiko Iwasaki, the research tracked 42 participants diagnosed with post-vaccination syndrome (PVS)—a condition not yet officially recognized by major health bodies like the CDC or WHO—alongside 22 healthy vaccinated controls. The study found that in some PVS patients, detectable levels of spike protein remained in their blood for between 600 and 700 days post-vaccination. This sharply contrasts with earlier claims from federal health agencies, such as the FDA and CDC, which stated that the spike protein produced by mRNA vaccines is cleared from the body within about eight weeks and poses no significant health risk.

The persistence of this vaccine-induced spike protein is notable because it mirrors findings in long COVID patients, where viral spike protein lingers after infection. In the Yale study, PVS participants—who reported chronic symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, and neurological issues after vaccination but had no history of COVID-19 infection—exhibited not only higher circulating spike protein levels but also distinct immunological signatures. These included elevated levels of inflammatory markers and altered immune cell activity, suggesting a prolonged immune response potentially triggered by the lingering spike protein. The researchers hypothesize that this could be a mechanism behind PVS, a condition that shares symptomatic overlap with long COVID but is uniquely linked to vaccination rather than viral infection.

The article highlights that these findings challenge the narrative promoted by federal health authorities during the vaccine rollout. For instance, the FDA had previously dismissed concerns about spike protein persistence or toxicity as misinformation, a stance that influenced public health messaging and even justified social media censorship of vaccine injury discussions. Platforms like X (before its shift under Elon Musk’s leadership) and others reportedly suppressed accounts raising questions about vaccine side effects, often labeling such content as misleading based on official assurances. The Yale study, however, lends credence to some of these silenced concerns, suggesting that vaccine-related complications may be underreported or inadequately studied.

The research methodology involved sensitive blood tests to detect spike protein and immune profiling to compare PVS patients with healthy controls. While the sample size of 42 PVS participants is relatively small, the findings are statistically significant within the study’s scope and align with anecdotal reports from vaccine-injured individuals who have struggled to gain medical recognition. The authors emphasize that PVS appears to affect only a small minority of vaccinated people, with the vast majority experiencing no long-term issues. Nonetheless, they argue that the condition warrants further investigation, especially given the global scale of mRNA vaccine administration—billions of doses have been given worldwide.

The article also contextualizes the study within a broader debate about vaccine safety and transparency. It notes that the preprint status means the research has not yet undergone peer review, a critical step for validation in the scientific community. Critics might argue that its conclusions are premature, but the authors counter that the urgency of understanding potential vaccine injuries justifies sharing preliminary results. The study’s release comes amid growing acknowledgment of rare vaccine side effects, such as myocarditis, and follows other research, like a Japanese study cited in the article, which similarly found prolonged spike protein presence in some vaccinated individuals.

Finally, the Just The News piece underscores the social and political implications. It references the reinstatement of X accounts discussing vaccine injuries post-Musk acquisition, signaling a shift in how such topics are handled online. The Yale findings could fuel calls for more robust post-vaccination monitoring and recognition of PVS as a legitimate diagnosis, potentially reshaping public trust in health institutions that have downplayed these risks. While the study doesn’t question the overall efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines, it highlights the need for a nuanced conversation about their safety profile in rare cases.

Dig In JustTheNews.com